Bajirao and Mastani: A Love Story That Defied an Empire

The monsoon clouds gathered over Pune in the year that would test the Maratha Empire’s greatest military mind in ways no battlefield ever could. Bajirao I, the 7th Peshwa of the Maratha Empire, stood in the corridors of Shaniwar Wada, the seat of Peshwa power, facing a battle that his legendary tactical genius could not win through strategy alone. This was not a confrontation with the Mughals he had so brilliantly outmaneuvered, nor the Nizam whose forces he had repeatedly defeated. This was a war against the very society he served—a conflict between the heart and the throne, between personal desire and public duty, between the man and the office he held.

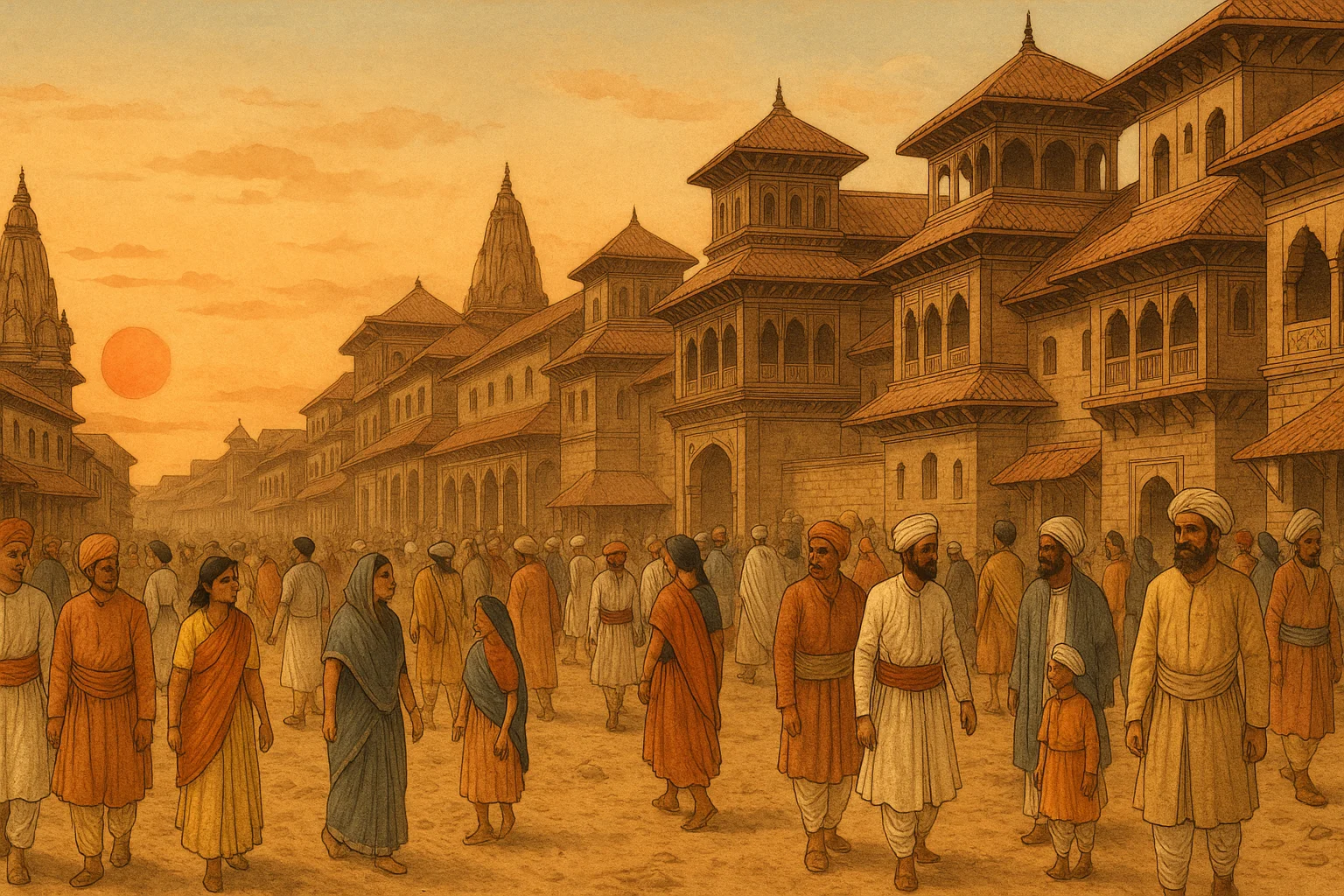

The story of Bajirao and Mastani has echoed through centuries, inspiring ballads, films, and endless debate. It is a narrative that reveals the profound tensions within Indian society of the 18th century—tensions between different religious communities, between rigid social hierarchies and human emotion, between the public persona required of leaders and their private selves. To understand this love story is to understand not merely two individuals, but the entire complex world of the Maratha Empire at its zenith, when it was transforming from a regional power into the dominant force in the Indian subcontinent.

Historical accounts vary in their details, with some aspects embellished by romantic legend and others obscured by the passage of time and the biases of those who recorded them. Yet the core of the story remains: a Brahmin Peshwa, holder of one of the most powerful positions in India, defying convention for a love that society could not accept. The consequences of this defiance would ripple through his family, his administration, and ultimately through history itself.

The World Before

The early 18th century was a period of dramatic transformation across the Indian subcontinent. The mighty Mughal Empire, which had dominated northern India for nearly two centuries, was entering its twilight years. The death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707 had unleashed forces of decentralization that the empire’s weakened successors could not contain. Provincial governors declared independence, regional powers asserted themselves, and the carefully constructed edifice of Mughal authority began to crumble.

Into this vacuum stepped the Marathas, a confederation that had its origins in the resistance movement led by Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj in the previous century. By the time Bajirao assumed the position of Peshwa, the Maratha Empire had evolved from a regional kingdom into an expanding power with ambitions that stretched from the Deccan to the heart of northern India. The Peshwa—literally “the foremost”—had become the empire’s chief minister and military commander, wielding authority that in many ways eclipsed that of the Chhatrapati, the nominal head of state.

This was a world of constant warfare, shifting alliances, and complex political maneuvering. The Marathas faced challenges from multiple directions: the remnants of Mughal authority still commanded respect and resources in Delhi; the Nizam of Hyderabad sought to maintain his independence and territorial integrity in the Deccan; the Portuguese controlled coastal enclaves; and various other regional powers—from the Rajputs to the emerging powers in Bengal—all played their parts in the great game of Indian politics.

Within this turbulent landscape, the Maratha Empire itself was far from monolithic. It was a confederation of powerful families and sardars (nobles), each commanding their own forces and territories. The Holkars, Scindias, Gaekwads, and Bhonsles were semi-autonomous powers who acknowledged the Peshwa’s leadership while jealously guarding their own prerogatives. Managing these internal dynamics required diplomatic skill equal to any military campaign.

The society over which Bajirao presided as Peshwa was deeply hierarchical, governed by intricate rules of caste, community, and religious observance. The Peshwa himself came from the Chitpavan Brahmin community, a group that had risen to prominence through their association with the Peshwa office. As Brahmins—the priestly caste at the apex of the varna system—they were expected to maintain the highest standards of ritual purity and orthodox religious practice. This expectation was not merely personal but political: the Peshwa’s legitimacy derived in part from his position as the upholder of dharma and proper social order.

Marriage alliances in this world were carefully calculated political acts. They cemented relationships between powerful families, created networks of obligation and support, and reinforced social hierarchies. The idea of marriage based primarily on romantic love—particularly crossing community boundaries—was largely alien to this system. Marriages were arranged within the community, preferably within subcastes, and love, when it came, was expected to follow rather than precede the marriage ceremony.

Yet this rigid social structure coexisted with a society in constant motion. The Maratha expansion brought diverse peoples under its umbrella: Hindus and Muslims, Brahmins and warriors, merchants and farmers. The army itself was a melting pot where caste distinctions, while never forgotten, were sometimes subordinated to military necessity. This tension between orthodox social prescriptions and practical realities created the space in which unconventional relationships could form—even as they also ensured that such relationships would face fierce opposition.

The Players

Bajirao I came to the office of Peshwa at the remarkably young age of twenty, succeeding his father Balaji Vishwanath in 1720. This was not merely inherited position—the young Bajirao had already demonstrated the qualities that would make him one of India’s greatest military commanders. His appointment as the 7th Peshwa of the Maratha Empire placed enormous responsibility on his shoulders, responsibility he would fulfill with a brilliance that transformed the Maratha state.

As Peshwa, Bajirao was not merely a military commander but the chief administrator of the empire. He managed the complex relationships between different Maratha sardars, conducted diplomacy with other Indian powers, oversaw revenue collection, and led armies in the field. Historical records from this period show a man of formidable energy, capable of marching his cavalry across vast distances and then engaging in detailed administrative work. He was known for his innovative military tactics, particularly his use of swift cavalry movements to outmaneuver larger, more cumbersome enemy forces.

But Bajirao was also a man of his times, shaped by the expectations and limitations of his position. As a Chitpavan Brahmin serving as Peshwa, he bore the weight of his community’s orthodox expectations. He was married to Kashibai, a match arranged in accordance with social custom, connecting prominent families within the Brahmin community. By all accounts, this was initially a successful marriage that produced sons and fulfilled the social and political functions such unions were designed to serve.

Yet beneath the public persona of the brilliant Peshwa lay a more complex individual. The exact circumstances of how Bajirao met Mastani remain shrouded in legend and competing historical narratives. Tradition holds that he encountered her during one of his military campaigns, though the specifics—whether during a campaign against the Nizam or in another context—vary in different accounts. What is clear from the historical record is that a relationship developed that would challenge every convention of the society Bajirao led.

Mastani herself remains a somewhat enigmatic figure, viewed through the lens of sources often hostile to her presence at the Peshwa’s court. Different accounts describe her variously as a princess, a court dancer, or a warrior—descriptions that may all contain elements of truth or may reflect the biases and imaginations of those recording her story. What is certain is that she was not from the Chitpavan Brahmin community, making any formal relationship with the Peshwa socially transgressive in the eyes of orthodox society.

The religious identity attributed to Mastani in various accounts adds another layer of complexity to the story. Some sources describe her as Muslim, others as the daughter of a Rajput mother and Muslim father, still others provide different genealogies entirely. In the rigidly compartmentalized religious landscape of 18th-century India, these questions of identity were not merely personal but carried enormous social and political weight. The exact truth, lost to history, may be less important than understanding that Mastani represented—in the eyes of Bajirao’s family, his Brahmin advisors, and much of Maratha society—an unsuitable match that threatened social order and religious propriety.

The relationship between Bajirao and Mastani, as it developed, placed both individuals in impossible positions. For Bajirao, it meant choosing between personal happiness and the expectations of his position, between his feelings and his duty to family and community. For Mastani, it meant entering a world where she would never be fully accepted, where her presence would be seen as a threat, and where every moment would be a struggle against social ostracism.

Rising Tension

The first signs of conflict emerged gradually, like cracks appearing in a palace wall before an earthquake. When Bajirao’s relationship with Mastani became known to his family and the wider Brahmin community in Pune, it triggered a reaction that went far beyond mere family disapproval. This was seen as a threat to the very foundations of Maratha society and the legitimacy of the Peshwa’s authority.

Bajirao’s mother, Radhabai, and his brother, Chimaji Appa, led the family opposition to the relationship. Their concerns were not simply personal—though the hurt to Kashibai, Bajirao’s first wife, was certainly a factor—but reflected deeper anxieties about social propriety and political legitimacy. In their view, the Peshwa’s position carried responsibilities that extended beyond personal happiness. As the premier Brahmin in the Maratha Empire, the Peshwa was expected to be the exemplar of orthodox practice and proper social behavior. A relationship that crossed community boundaries threatened to undermine this image and, by extension, the Peshwa’s authority.

The Chitpavan Brahmin community of Pune, whose fortunes were intimately tied to the Peshwa office, viewed Mastani’s presence as particularly problematic. According to the Hindu texts and practices they held authoritative, questions of marriage and social mixing were governed by strict rules. The concept of ritual purity was not merely abstract theology but a daily practice that governed everything from food preparation to social interaction. Mastani’s presence in the Peshwa’s household was seen as a contamination of these carefully maintained boundaries.

The historical sources suggest that attempts were made to separate Bajirao and Mastani, though the exact nature of these attempts varies in different accounts. Some traditions hold that Mastani was at times confined or kept under house arrest when Bajirao was away on military campaigns. Other accounts describe attempts to discredit her character or to convince Bajirao to send her away. The family reportedly appealed to his sense of duty, to his responsibilities to his sons by Kashibai, to the expectations of his position.

Bajirao found himself trapped between irreconcilable demands. On one side stood the woman he loved, reportedly living in a residence he had built for her, bearing him a son—a child who would face his own struggles for acceptance in Maratha society. On the other stood his family, his community, the orthodox establishment whose support was crucial to his political authority, and the weight of social expectation that defined his world.

The Court’s Dilemma

The Maratha court in Pune during this period was a place of elaborate ritual and careful hierarchy. The Peshwa’s durbar—the formal court where he conducted state business—was governed by protocols that reflected and reinforced social distinctions. Where one sat, in what order one was received, what honors one was shown—all these communicated status and power. Into this carefully ordered world, Mastani’s presence introduced chaos.

The question of Mastani’s status at court became a flashpoint for broader tensions. Should she be received as the Peshwa’s wife? But she had not undergone the formal marriage ceremonies recognized by Brahmin orthodoxy. Should she be given apartments in the Peshwa’s palace? But this would be seen as granting her a legitimacy that orthodox society refused to recognize. Should her son be acknowledged as the Peshwa’s heir? But to do so would be to break the rules governing inheritance and succession.

These were not abstract questions but daily challenges that the Peshwa’s household had to navigate. Traditional accounts describe Kashibai’s dignity in the face of what must have been a personally painful situation, maintaining her position as the recognized wife while Bajirao’s attention was elsewhere. The sources also suggest that despite the family’s opposition, Bajirao refused to abandon Mastani or deny their relationship.

The conflict played out not only in family confrontations but in the whispered conversations of courtiers, in the correspondence between Maratha nobles, in the gossip that traveled through the bazaars of Pune. The Peshwa’s personal life had become a public scandal, one that threatened to undermine respect for his office at a time when the Maratha Empire faced challenges on multiple frontiers.

The Military Complications

Even as these domestic dramas unfolded, Bajirao continued to fulfill his responsibilities as the supreme military commander of the Maratha Empire. The historical record shows that during this period, he conducted multiple campaigns, engaged in complex diplomatic negotiations, and managed the often-fractious relationships between different Maratha sardars. His military genius remained undiminished—the same tactical brilliance, the same capacity for bold strokes and swift movements that had made him famous.

Yet the tension in his personal life cast a shadow over these achievements. Some accounts suggest that Bajirao took Mastani with him on certain campaigns, a further breach of convention that scandalized his more orthodox associates. Whether true or embellished by later storytellers, such stories reflect the fundamental contradiction at the heart of Bajirao’s life: a man bound by the conventions of his position yet willing to defy those same conventions in matters of the heart.

The question that hung over the Peshwa’s court was how this situation could be resolved. Bajirao showed no inclination to abandon Mastani, despite all pressure from family and community. Yet he could not fully legitimize the relationship without provoking a complete break with orthodox society. The result was a state of permanent tension, a situation that satisfied no one and that threatened to destabilize the careful political balance on which the Peshwa’s power rested.

The Turning Point

The crisis, when it came, was not a single dramatic confrontation but rather the cumulative weight of irreconcilable pressures. Bajirao I, the 7th Peshwa of the Maratha Empire, found himself engaged in the most complex campaign of his career—not against external enemies but against the expectations and demands of the society he led. This was a battle that his renowned tactical genius could not win through clever maneuvering or bold cavalry charges.

The family’s opposition to Mastani remained implacable. According to various historical accounts, Bajirao’s mother Radhabai and brother Chimaji Appa continued to refuse acceptance of the relationship. The sources suggest that during Bajirao’s absences on military campaigns, Mastani faced active hostility from the Peshwa’s household. Some traditions hold that she was confined to her residence, treated not as the Peshwa’s consort but as a prisoner or unwelcome guest in Pune.

The birth of Mastani’s son—who would later be known as Shamsher Bahadur—added urgency to the conflict. The question of this child’s status was not merely a family matter but a political one with implications for succession and authority. Orthodox Brahmin society refused to recognize the boy as having the same status as Bajirao’s sons by Kashibai. Yet Bajirao, by various accounts, showed affection for this child and sought to provide for his future.

The exact sequence of events remains debated by historians, with different accounts providing varying details. What is clear from the historical record is that the situation created enormous stress on all parties involved. Bajirao was reportedly torn between his duties as Peshwa—which required maintaining the support of orthodox Brahmin society—and his personal attachments. Mastani lived in a gilded cage, protected by the Peshwa’s power but isolated by social rejection. Kashibai maintained her position as recognized wife while watching her husband’s attention devoted elsewhere. The family struggled to protect what they saw as the honor and legitimacy of the Peshwa office while their pleas went unheeded.

The political implications extended beyond the immediate family drama. Other Maratha nobles and sardars watched these events with concern and calculation. Some may have sympathized with Bajirao’s personal situation; others saw an opportunity to advance their own positions at the expense of a Peshwa whose personal life had become controversial. The carefully maintained balance of power within the Maratha confederacy depended partly on respect for the Peshwa’s authority—an authority potentially undermined by the scandal surrounding his household.

Bajirao’s military campaigns during this period took him across vast distances, from confrontations with Mughal forces in northern India to engagements with the Nizam in the Deccan. The historical record shows a commander still at the height of his powers, achieving victories that expanded Maratha influence and filled the empire’s treasury. Yet one wonders what thoughts occupied his mind during the long marches between battles—whether he found the clarity in military life that eluded him in the complex emotional and social terrain of Pune.

Aftermath

The resolution of the conflict between Bajirao’s personal life and his public role came not through reconciliation or compromise but through mortality itself. Bajirao I died in 1740, at the relatively young age of forty, during a military campaign. The exact circumstances of his death remain somewhat unclear in the historical sources, but he passed away far from Pune, the capital where so much of the drama of his personal life had unfolded.

His death removed the one figure whose authority and position had protected Mastani from the full force of social rejection. The historical record suggests that after Bajirao’s death, Mastani’s situation became even more precarious. According to some accounts, she died shortly after learning of the Peshwa’s death, though the exact circumstances vary in different traditions. Some sources suggest suicide out of grief, others a death from natural causes, still others are vague about the details. What is certain is that without Bajirao’s protection, her position in Pune became untenable.

The fate of their son, Shamsher Bahadur, reflects the complex dynamics of Maratha society. Rather than being completely cast out, he was eventually incorporated into the Maratha military establishment, though not with the status that would have been his as the acknowledged son of a Peshwa. He fought in various campaigns and apparently earned respect for his military abilities, but he remained marked by the circumstances of his birth, never fully accepted by orthodox society yet not entirely rejected either.

Bajirao was succeeded as Peshwa by his son Balaji Bajirao, born to his wife Kashibai. The transition of power proceeded smoothly, suggesting that despite the personal turmoil, Bajirao had maintained the political structures and alliances necessary for continuity. The new Peshwa inherited an empire at the height of its power, with territories and influence that stretched across much of India—a testament to Bajirao I’s military and administrative achievements despite the complications in his personal life.

The Maratha Empire itself would continue to expand for some years after Bajirao’s death, reaching its maximum extent in the mid-18th century. Yet it also faced growing challenges—the complexity of governing vast territories, the centrifugal forces within the confederacy, and ultimately the disastrous Third Battle of Panipat in 1761, which would devastate Maratha power in northern India. Whether Bajirao, had he lived longer, might have navigated these challenges differently remains one of history’s unanswerable questions.

Legacy

The story of Bajirao and Mastani endured in popular memory long after both protagonists had passed into history. It became the subject of ballads, theatrical performances, and later films and novels. Each era has retold the story in ways that reflect its own concerns and values—sometimes as a romantic tragedy, sometimes as a cautionary tale about the dangers of passion overwhelming duty, sometimes as an indictment of social rigidity.

In assessing Bajirao I’s historical significance, his relationship with Mastani is both central and peripheral. It is central because it reveals so much about the man beneath the role of Peshwa—his willingness to defy convention, his capacity for loyalty despite enormous pressure, the way personal desire and public duty warred within him. These qualities help explain both his greatness as a military commander—requiring boldness and willingness to break with conventional wisdom—and the tragedy of his personal life.

Yet the relationship is also peripheral to Bajirao’s main historical legacy, which rests on his achievements as the 7th Peshwa of the Maratha Empire. His military campaigns, his administrative innovations, his role in transforming the Marathas from a regional power into the dominant force in 18th-century India—these would have secured his place in history even without the romance with Mastani. The fact that he accomplished so much while navigating such turbulent personal circumstances makes the achievement all the more remarkable.

The story also serves as a window into the social dynamics of 18th-century India. It reveals the power of caste and community boundaries, the way marriage and family were enmeshed with politics and power, the limited spaces available for individual choice within a rigidly structured society. At the same time, it shows that even within these constraints, individuals found ways to assert their desires and make choices that society condemned—and that they paid prices for doing so.

For later generations, the tale of Bajirao and Mastani has served multiple functions. For some, it represents the tragedy of love thwarted by social convention—a narrative that resonated particularly strongly as Indian society in later periods grappled with questions about arranged versus love marriages, intercommunity relationships, and the balance between individual choice and family expectation. For others, it illustrates the importance of maintaining social boundaries and the chaos that results when leaders fail to uphold them.

Modern retellings of the story, particularly in films and popular culture, have often emphasized the romantic elements while sometimes downplaying or simplifying the complex social and religious issues at stake. These versions tend to portray Mastani more sympathetically than did many historical sources, presenting her as a victim of prejudice rather than as a disruptive force. They also tend to emphasize Bajirao’s love and loyalty, sometimes at the expense of acknowledging the real harm his choices caused to others, particularly Kashibai.

The architectural legacy of this period provides physical reminders of the story. The structures associated with both Kashibai and Mastani in Pune, though modified or rebuilt over time, mark the landscape of the city. Shaniwar Wada, the great palace of the Peshwas, stands as a monument to the power and authority that Bajirao wielded—a power that proved insufficient to overcome social convention in his personal life.

What History Forgets

In the shadow of the grand romance and dramatic conflicts, certain aspects of the story receive less attention than they deserve. The perspective of Kashibai, Bajirao’s first wife, is often reduced to a few conventional phrases about her dignity and forbearance. Yet she was a woman in an impossible situation—seeing her husband’s affections directed elsewhere, dealing with the social embarrassment this caused, yet maintaining her role as the Peshwa’s recognized wife. She raised sons who would play significant roles in Maratha history, managed her position with apparent grace, and navigated circumstances not of her choosing with remarkable skill.

The broader family dynamics also deserve more attention. Bajirao’s brother Chimaji Appa was himself a capable military commander who supported his brother’s campaigns while opposing his personal choices. The relationship between the brothers apparently survived this fundamental disagreement, suggesting that bonds of family and shared purpose could coexist with deep disagreement about personal matters. Bajirao’s mother Radhabai faced the challenge of trying to guide a son whose power and position far exceeded her own while feeling that his choices threatened everything she valued.

The position of the other women in Mastani’s life—servants, companions, or whatever support network she might have had—remains entirely obscure in the historical record. Yet she must have had some circle of support, some people who showed her kindness in what must have been an often hostile environment. Their stories, their perspectives, their choices to maintain loyalty to a woman rejected by most of society—these are lost to history, visible only in their absence.

The response of the ordinary people of Pune to the drama unfolding in the Peshwa’s household is also largely unrecorded. Did they gossip about it in the markets? Did some sympathize with the romance while others shared the orthodox establishment’s disapproval? How did the presence of Mastani affect the delicate communal balance in a city that was home to Hindus and Muslims, Brahmins and other castes, merchants and warriors? The surviving sources, written largely by and for the elite, tell us little about these popular reactions.

Finally, the story of Shamsher Bahadur, Bajirao and Mastani’s son, deserves more attention than it typically receives. He grew up marked by circumstances beyond his control, achieving a position in Maratha military service while never escaping the shadow of his birth. His own feelings about his parents, his relationship with his half-brothers, his experience of being simultaneously part of and excluded from the highest circles of Maratha society—these are questions that the historical record leaves largely unanswered but that would tell us much about the human cost of his parents’ choices.

The story of Bajirao and Mastani ultimately resists simple interpretation. It is neither pure romance nor simple tragedy, neither heroic defiance of unjust social rules nor reckless disregard for legitimate social concerns. It is, instead, a deeply human story about people caught in circumstances that offered no good solutions—only choices between different kinds of pain, different betrayals of different loyalties. The fact that it occurred at the highest levels of the Maratha Empire, involving the 7th Peshwa himself, ensured that it would be remembered, but the fundamental conflicts it reveals—between duty and desire, between social expectation and personal happiness, between the roles we are assigned and the lives we wish to lead—are universal and timeless.

In the end, what makes the story of Bajirao and Mastani compelling across the centuries is not merely the romance or the drama, but the way it illuminates the complex humanity of historical figures often reduced to mere names and dates. Bajirao I was not just the 7th Peshwa of the Maratha Empire, a military genius who never lost a battle. He was also a man who loved against the dictates of his society, who tried to fulfill impossible demands, who achieved greatness in the public sphere while finding only heartbreak in private life. That tension—between the public figure and the private person, between what history records and what was actually experienced—is what makes the story resonate long after the principals have passed into legend.