Lost Cities of the Indus: When Civilization Vanished

The archaeologist’s trowel scraped against something solid beneath the Pakistani soil. It was not the first brick she had found that morning in 1920, but this one was different. Perfectly fired, remarkably uniform, part of a wall that stretched in a straight line beneath the earth. As her team carefully excavated, more walls emerged—streets laid out in precise grids, drainage systems of sophisticated engineering, buildings constructed with a standardization that spoke of central planning and urban expertise. But there were no inscriptions identifying the builders, no monumental temples proclaiming their gods, no royal tombs declaring their kings. Just silence, and the mystery of a civilization that had vanished so completely that even its name was forgotten.

What they had discovered would eventually be recognized as the Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the Harappan Civilization, one of the three earliest civilizations in the world alongside ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. But unlike those contemporary cultures whose stories had been passed down through texts and traditions, the Indus civilization had disappeared into such profound obscurity that millennia passed before anyone even knew it had existed. The cities stood empty, their streets gradually buried by time, their people scattered to unknown destinations, their written language never deciphered, their fate unknown.

The excavations would reveal an astonishing truth: this was no minor culture that had flickered briefly and died. The Indus Valley Civilization was the most widespread of the three great Bronze Age civilizations, spanning much of Pakistan, northwestern India, and even northeast Afghanistan. It had flourished for nearly two thousand years, from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, reaching its mature urban peak from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. For over seven hundred years, its cities thrived with populations, trade, sophisticated urban planning, and a quality of life that would not be matched in the region for millennia after its fall. And then, around 1900 BCE, something happened. The story of what caused this vast civilization to collapse and vanish remains one of archaeology’s most haunting mysteries.

The World Before

The Bronze Age was humanity’s first age of cities, when scattered farming villages began coalescing into urban centers with populations in the thousands. Around 3300 BCE, in three separate regions of the ancient world, this transformation reached a critical mass that created true civilizations—complex societies with specialized labor, social hierarchies, long-distance trade, monumental architecture, and systems of writing. In the Nile Valley, Egyptian civilization was taking shape under its first pharaohs. In Mesopotamia, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian city-states were developing cuneiform writing and building ziggurats to their gods. And in South Asia, along the fertile floodplains of the Indus River and its tributary systems, a third great civilization was emerging.

The geography of this third civilization was remarkable in its extent and diversity. The Indus River flows through the length of Pakistan, from the Himalayas in the north to the Arabian Sea in the south, creating a vast alluvial plain. But the civilization that grew here was not confined to this single river system. It also flourished along a network of perennial monsoon-fed rivers that once coursed in the vicinity of the Ghaggar-Hakra, a seasonal river in northwest India and eastern Pakistan. This dual river system provided the civilization with extensive agricultural lands, reliable water sources, and natural highways for transportation and trade.

The environmental conditions of this era were more favorable than they are today. The monsoon patterns were stronger and more reliable, the rivers fuller, the vegetation more abundant. The people who settled here around 3300 BCE found a landscape capable of supporting large, permanent populations. They domesticated crops suited to the climate, developed irrigation techniques, and began the gradual process of building permanent settlements.

By 2600 BCE, these settlements had evolved into something unprecedented in South Asian history: true cities. These were not merely large villages but planned urban centers with populations numbering in the tens of thousands. The transformation from scattered farming communities to sophisticated urban civilization happened relatively rapidly in archaeological terms, suggesting either rapid indigenous development, cultural exchange with Mesopotamia and Egypt, or most likely a combination of both.

The world of 2600 BCE was one of increasing interconnection. Trade routes were expanding, connecting distant civilizations. Egyptian ships sailed to the Levant; Mesopotamian merchants traded with cities in the Persian Gulf. Into this network, the Indus civilization inserted itself, trading its goods—cotton textiles, semi-precious stones, copper, and luxury items—for Mesopotamian silver, tin, and other commodities. Archaeological evidence from Mesopotamian sites includes seals and artifacts of unmistakable Indus origin, proving that these civilizations, separated by thousands of miles, were in commercial contact.

Yet the Indus civilization developed along its own distinct trajectory. Unlike Egypt with its god-kings and massive pyramids, or Mesopotamia with its competing city-states and towering ziggurats, the Indus cities showed remarkably uniform culture across vast distances, little evidence of monarchical power, and no obvious temples or palaces dominating the urban landscape. Their cities were characterized instead by practical urban planning, efficient drainage systems, standardized bricks, and what appears to have been a relatively egalitarian social structure—at least compared to the stark hierarchies visible in contemporary Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The Cities Rise

The mature phase of the Indus Valley Civilization, from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE, represents one of the most successful urban experiments in human history. The archaeological evidence reveals cities of remarkable sophistication, built with a level of planning and engineering that would not be seen again in South Asia for thousands of years.

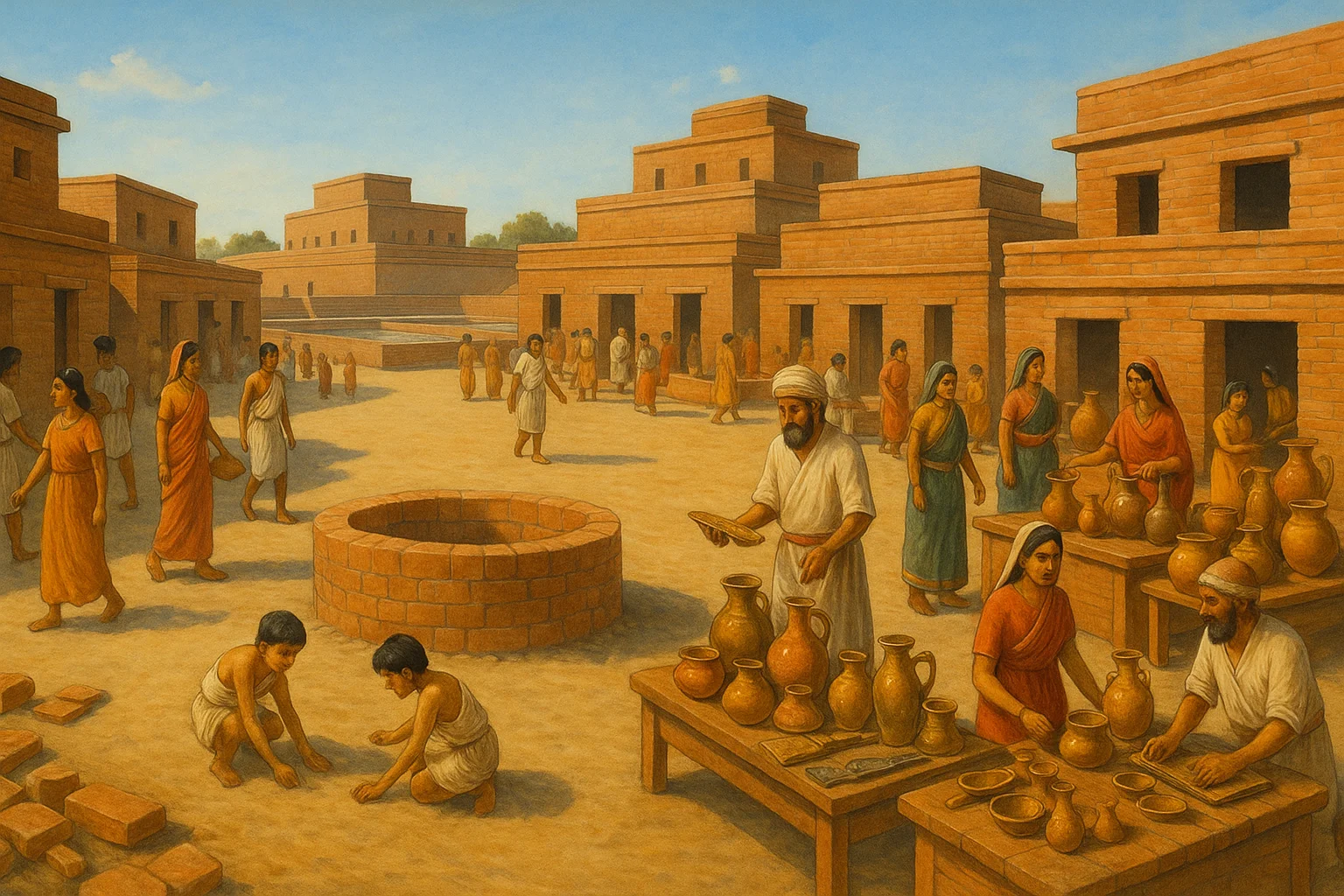

The cities followed similar patterns regardless of their location across the vast territory of the civilization. They were built primarily of standardized fired bricks, with dimensions that remained consistent across different sites—a uniformity that speaks to centralized standards or extensive cultural exchange. The streets were laid out in precise grid patterns, with main thoroughfares running north-south and east-west, intersecting at right angles. This orthogonal planning created regular city blocks, a level of urban organization that contemporary cities in Egypt and Mesopotamia did not achieve.

Perhaps most impressive was the attention to sanitation and water management. The cities featured sophisticated drainage systems, with covered drains running along the streets, connected to private drains from individual houses. Wells were constructed throughout the residential areas, providing decentralized access to clean water. Some structures identified as public baths suggest a culture that valued cleanliness and perhaps ritual bathing. The quality of urban infrastructure was extraordinary—these were cities designed not just for monuments and palaces, but for the practical needs of ordinary residents.

The material culture reveals a society with skilled craftspeople and extensive trade networks. Artisans produced fine pottery, carved seals from steatite (a soft stone), created jewelry from semi-precious stones like carnelian and lapis lazuli, worked copper and bronze, and wove cotton textiles. The famous seals, typically square or rectangular, bore intricate carvings of animals—bulls, elephants, tigers, rhinoceros—and symbols from an undeciphered script. These seals were likely used in trade, pressed into clay to mark ownership or certify goods.

The agricultural foundation of the civilization was robust. The fertile alluvial soils, replenished by annual floods, supported cultivation of wheat, barley, peas, sesame, and cotton. The evidence suggests that the Indus people were among the first to cultivate cotton for textiles, a crop that would later become central to the Indian economy. They domesticated cattle, sheep, goats, and possibly chickens. The combination of reliable agriculture and extensive trade created the economic surplus necessary to support large urban populations and specialized craftspeople.

Yet for all their achievements, the Indus cities remain enigmatic. Unlike Mesopotamian cities with their monumental temples and royal inscriptions, or Egyptian cities dominated by temples and tombs of pharaohs, the Indus cities show remarkably little obvious evidence of centralized religious or political power. There are structures that may have been administrative centers or temples, but nothing on the scale of a Mesopotamian ziggurat or Egyptian pyramid. No royal tombs laden with treasure have been found. No inscriptions proclaim the deeds of kings or priests.

This absence has led to scholarly debate about the nature of Indus society. Was it governed by merchant councils rather than kings? By priests who left no monumental traces? By multiple small authorities rather than centralized power? Was it remarkably egalitarian, or do we simply not yet recognize the markers of their hierarchy? The undeciphered script offers no answers; until it is translated, if it ever is, the political and religious life of the Indus people remains largely mysterious.

What is clear is that for over seven hundred years, from approximately 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE, this urban civilization flourished. Cities were maintained, trade continued, the standardized culture persisted across hundreds of miles. It was a period of stability and prosperity unmatched in South Asian prehistory. And then, as the second millennium BCE began, something changed.

The Signs of Trouble

The archaeological record of the period around 1900 BCE tells a story of transformation and decline, though the details remain debated and the causes uncertain. What is clear is that the mature Indus civilization, with its characteristic urban features, began to fragment and eventually disappeared.

The evidence suggests the changes were neither sudden nor uniform across the civilization’s vast territory. Different cities showed different patterns. Some were abandoned gradually, with signs of declining maintenance and population. Streets that had been carefully kept clean for centuries began to show accumulation of debris. Drainage systems fell into disrepair. Building standards declined, with cruder construction replacing the careful brickwork of earlier periods. These are signs not of catastrophic destruction, but of gradual decay—a civilization losing the organizational capacity or resources to maintain its urban infrastructure.

In some locations, the archaeological evidence shows what scholars call a “de-urbanization” process. The characteristic features of urban life—the grid-pattern streets, the public infrastructure, the standardized buildings—gave way to more haphazard construction. Smaller structures were built in formerly public spaces. The careful urban planning that had defined the civilization for centuries was abandoned. This suggests not external invasion or natural catastrophe, but internal breakdown of the systems that had maintained urban life.

Importantly, there is little evidence of violent destruction at the major Indus sites. Unlike cities conquered in warfare, there are no layers of ash from burning, no mass graves, no weapons scattered in the streets, no signs of fortifications being breached. If the Indus civilization fell to invasion, the invaders left remarkably little archaeological trace. This absence of violence suggests that warfare, while possible, was not the primary cause of the civilization’s end.

The population patterns also changed. Some cities were abandoned entirely, their residents departing for unknown destinations. But the population didn’t simply vanish—archaeological evidence suggests migration and dispersal. Smaller, more rural settlements increased in some regions, particularly to the east and south. It appears that rather than being destroyed, the urban population fragmented and relocated, reverting to smaller-scale, village-based life.

Trade networks that had connected the Indus to Mesopotamia and other distant regions appear to have contracted or ceased. Mesopotamian texts that previously mentioned trade with regions that may have been the Indus civilization fall silent. The distinctive Indus seals disappear from Mesopotamian archaeological sites. This suggests either that the Indus civilization could no longer participate in long-distance trade, or that the trade routes themselves were disrupted.

The question that has haunted archaeologists since the discovery of this civilization is simple yet profound: why? What could cause such a vast, successful, long-lived civilization to collapse and fragment? What force or combination of forces could end two millennia of cultural continuity and urban life?

Theories of Collapse

The mystery of the Indus civilization’s decline has generated numerous theories, each attempting to explain how and why these cities were abandoned. The challenge is that without deciphered texts, without historical records, archaeologists must reconstruct the story from material remains alone—a difficult task when trying to understand processes that unfolded over decades or centuries.

One early theory, now largely discredited, proposed invasion by Indo-Aryan peoples entering the region from Central Asia. This theory was based partly on later Vedic texts that described conquest of fortified cities and partly on archaeological evidence that was initially misinterpreted as signs of violence. However, more careful analysis has shown that the timeline doesn’t match—the Indus cities declined before the proposed dates of Indo-Aryan migration. Moreover, the absence of destruction layers and the gradual nature of the decline argue against sudden military conquest. While population movements may have played some role in the civilization’s transformation, invasion does not appear to have been the primary cause of urban collapse.

Climate change presents a more compelling explanation. The period around 2000-1900 BCE corresponds to known climate shifts in South Asia. Research suggests that the monsoon patterns that had sustained the civilization’s agriculture may have weakened or become more erratic. The Indus and its tributary rivers likely carried less water. Most significantly, the river system associated with the Ghaggar-Hakra appears to have dried up or dramatically reduced flow during this period, possibly due to tectonic changes that altered drainage patterns.

For a civilization dependent on reliable water sources and productive agriculture, such environmental changes would have been catastrophic. Crop failures would have led to food shortages. Reduced river flow would have impacted both agriculture and trade, as rivers served as transportation routes. Cities that had grown large based on agricultural surplus would have struggled to feed their populations. The archaeological evidence of declining urban infrastructure and maintenance could reflect a society under increasing environmental stress, unable to sustain the complexity of urban life.

The drying of rivers would have forced populations to migrate in search of water and arable land. This could explain the pattern of urban abandonment and the movement of population toward the Gangetic plain to the east and toward Gujarat to the south, regions that may have offered better environmental conditions. It could also explain why the collapse was gradual rather than sudden—as environmental conditions deteriorated over decades, populations slowly dispersed, abandoning cities that could no longer be sustained.

Another factor may have been the breakdown of trade networks. If environmental changes in regions beyond the Indus affected trade partners, or if the reduced flow of rivers made transportation more difficult, the economic foundation of the urban centers would have eroded. Cities that depended on trade for essential resources like metals, or that derived wealth from manufacturing and exporting goods, would have declined as trade contracted.

Disease is another possibility that cannot be ruled out. Large urban populations living in close quarters are vulnerable to epidemics, and Bronze Age populations had no defenses against many infectious diseases. However, disease typically leaves evidence in mass graves or unusual burial patterns, which have not been clearly identified at Indus sites. If disease played a role, it may have been as a secondary factor, affecting populations already weakened by environmental and economic stress.

The truth is likely some combination of these factors. Climate change altered the environmental conditions that had sustained the civilization. Agricultural productivity declined. Trade networks contracted. Cities became harder to maintain and provision. Population gradually dispersed, seeking better conditions elsewhere. The urban civilization transformed back into smaller-scale, rural societies. The process probably took several generations, with different regions experiencing the decline at different rates and in different ways.

What makes the Indus collapse particularly poignant is that there was no recovery. In Mesopotamia and Egypt, urban civilizations experienced collapses but eventually rebuilt. The Indus urban tradition, once lost, was not regained. The subsequent cultures of the region did not revive the grid-pattern cities, the sophisticated drainage systems, the standardized brick production, the distinctive seals and script. The knowledge and organizational systems that had sustained urban life for so long vanished with the cities.

The Long Forgetting

After 1900 BCE, the archaeological record shows a dramatic transformation in the former territories of the Indus civilization. The characteristic urban features disappeared. The distinctive pottery styles changed. The script, whatever it recorded, ceased to be used or was forgotten. The seals were no longer manufactured. The civilization had not only collapsed but had largely vanished from cultural memory.

Small rural settlements continued in some areas, and some scholars argue for cultural continuity in certain practices or beliefs that may have survived into later periods. Populations that had once lived in the cities presumably continued existing somewhere, carrying forward some aspects of their culture. But the urban civilization itself—the cities, the trade networks, the material culture, the organizational systems—was gone.

Over the following centuries and millennia, the abandoned cities gradually disappeared beneath layers of soil deposited by floods and time. The brick buildings, never rebuilt or maintained, slowly eroded. Vegetation grew over the ruins. Eventually, the sites became mounds in the landscape, remembered if at all as natural hills rather than the remains of human construction. Some sites may have retained vague associations with antiquity in local traditions, but the memory of the civilization that built them was lost.

The forgetting was so complete that when Alexander the Great marched through the region in the 4th century BCE, more than 1,500 years after the Indus cities flourished, neither he nor his chroniclers mentioned the ancient ruins. When Arab geographers and historians traveled through the region in medieval times, they noted monuments and cities from more recent eras but showed no awareness of the Bronze Age civilization. When the Mughal Empire ruled the region, no texts mentioned a great ancient civilization whose cities lay beneath the earth.

This stands in stark contrast to other ancient civilizations. Egypt’s monuments remained visible throughout antiquity and medieval times; their scale made them impossible to ignore even when their original purpose was forgotten. Mesopotamian sites, though buried, were associated with cities mentioned in biblical and classical texts, providing some continuity of memory. But the Indus civilization left no texts that were preserved in later traditions, no monuments whose scale defied forgetting, no clear connection to later historical cultures.

The Indus Valley Civilization remained unknown to modern scholarship until the 19th and early 20th centuries. British colonial surveyors and archaeologists, documenting monuments and archaeological sites across India, began to notice curious brick structures and artifacts in the Punjab and Sindh regions. Initially, these were not recognized as evidence of an ancient civilization. Some ruins were even used as sources of bricks for railroad construction, destroying invaluable archaeological evidence.

The breakthrough came in the 1920s when systematic excavations revealed the true nature and age of the sites. The discovery astonished the scholarly world. Here was a Bronze Age civilization as old as Egypt and Mesopotamia, one that had been completely forgotten, its very existence unsuspected. As excavations continued over subsequent decades, the extent and sophistication of the civilization became apparent. It was among the most remarkable archaeological discoveries of the 20th century—the recovery of an entire civilization from oblivion.

Voices from the Ruins

Even without deciphered texts, the archaeological remains speak to us across the millennia, offering glimpses into the daily lives of people who lived in these cities over four thousand years ago.

The standardized bricks tell us about a society that valued uniformity and planning, where building standards were maintained across vast distances. This suggests either strong cultural norms or some form of centralized control over production, though the nature of that control remains debated. The person who made bricks in one city was making them to the same dimensions as the brick-maker hundreds of miles away in another city—a remarkable consistency that required shared standards and probably shared measurement systems.

The drainage systems and wells speak to concerns about hygiene and water management. These were people who understood that human waste needed to be carried away from living spaces, who invested considerable labor in building and maintaining drainage infrastructure. The covered drains that ran along the streets, connected to drains from individual houses, represent a level of urban sanitation that would not be matched in the region until modern times. This suggests not only engineering knowledge but social organization capable of coordinating public infrastructure projects.

The seals, with their intricate animal carvings and undeciphered script, hint at commercial systems and perhaps bureaucratic record-keeping. Each seal is unique, suggesting they marked individual ownership or identity. The care taken in their manufacture—the detailed carving, the selection of specific animals or symbols—indicates they were important objects, possibly valuable in themselves beyond their practical function. That they have been found in Mesopotamian sites, thousands of miles away, confirms they were used in long-distance trade, perhaps as marks of authentication or quality.

The absence of obvious palaces, monumental temples, and royal tombs suggests something about social organization that differentiates the Indus civilization from its contemporaries. Were these societies less hierarchical? Were their leaders less concerned with monumental displays of power? Or did their religious and political structures simply express themselves in ways we don’t yet recognize? The relatively uniform size of houses in Indus cities, compared to the stark contrasts between elite and common dwellings in contemporary Egyptian and Mesopotamian cities, suggests a society with less extreme wealth inequality, though this interpretation remains debated.

The craft objects—the jewelry, the pottery, the copper and bronze tools—demonstrate skilled artisans producing both utilitarian and decorative items. The cotton textiles, though not preserved, are evidenced by spindle whorls and by later trade references. These were people who dressed in woven cloth, who adorned themselves with beads and ornaments, who valued both function and beauty in their material goods.

The children’s toys found at some sites—small carts with wheels, whistles, dice—remind us that these were living communities where children played, where people found moments of leisure even in their daily labors. It’s a humanizing detail, easy to overlook in discussions of urban planning and trade routes, but essential to remember: these were real people, with families and fears, hopes and frustrations, living their lives as fully as we live ours.

Legacy in Absence

The Indus Valley Civilization left no empire, founded no religion that survives today under that name, produced no texts that later civilizations could read and be influenced by. Its contribution to history is paradoxically found in its absence—in what was lost when it disappeared, and in the questions its ruins raise about civilization itself.

The urban planning and sanitation systems of the Indus cities would not be matched in South Asia for millennia. The careful grid layouts, the sophisticated drainage, the standardized construction—these innovations disappeared with the civilization and had to be reinvented much later. Future cities in the region grew more organically, without the systematic planning that characterized Indus urbanism. The loss represents a setback in urban development, a body of practical knowledge that vanished and had to be relearned.

Some scholars argue for cultural continuity between the Indus civilization and later Indian culture, though the connections are difficult to prove definitively without deciphered texts. Certain religious imagery found on Indus seals—figures in meditative poses, symbols that might represent early forms of later Hindu concepts—suggest possible connections, but these remain speculative. Agricultural practices, craft traditions, possibly even linguistic elements may have survived through the populations that dispersed after the urban collapse. But tracing these connections across the gap of centuries is challenging, and claims of direct continuity must be treated with caution.

What the Indus civilization definitively demonstrates is that urban civilization in South Asia is ancient, indigenous, and sophisticated. For much of modern history, South Asian civilization was understood primarily through the lens of the Vedic culture and later developments. The discovery of the Indus Valley Civilization proved that urban life in the region extends back to the Bronze Age, contemporary with and as sophisticated as the more famous civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia. This pushes back the timeline of complex society in South Asia by millennia and establishes it as one of the cradles of human civilization.

The collapse itself offers lessons about civilizational fragility. The Indus cities flourished for centuries, appearing stable and permanent. Yet they were vulnerable to environmental changes, dependent on systems—agricultural, commercial, organizational—that could break down. When those systems failed, the elaborate urban structure could not be maintained. The civilization that had seemed so successful unraveled within a few generations.

This vulnerability to environmental change has particular resonance today. The Indus civilization depended on reliable water sources and climatic stability. When climate patterns shifted and rivers diminished, the urban centers could not adapt and collapsed. In an era of anthropogenic climate change, the Indus example serves as a cautionary tale about the relationship between civilization and environment, about the risks of depending on conditions that can alter beyond our control.

The mystery itself—the undeciphered script, the uncertain causes of collapse, the questions about social organization—keeps the Indus civilization alive in scholarly imagination. Each new discovery, each new analytical technique, brings the possibility of answers. Recent advances in genetic analysis, climate science, and archaeological methods continue to provide new insights. The civilization refuses to remain entirely silent, revealing its secrets slowly through patient excavation and analysis.

The Unanswered Questions

More than a century after its discovery, the Indus Valley Civilization continues to guard its secrets. The script remains undeciphered, despite numerous attempts by scholars using various approaches. Unlike Egyptian hieroglyphics, which were decoded using the Rosetta Stone with its parallel texts in known languages, or Mesopotamian cuneiform, which could be approached through related languages, the Indus script has no such key. The inscriptions are typically short, found on seals and pottery, offering limited material for linguistic analysis. Without being able to read what the Indus people wrote, we cannot know their own names for their cities, their accounts of their history, their understanding of their world.

The political organization of the civilization remains uncertain. Was there a centralized state governing the entire civilization, or a network of independent cities sharing a common culture? Were there kings, councils, priests, or some other form of leadership? The apparent uniformity across such vast distances suggests some mechanism of cultural integration, but whether this was political, religious, economic, or simply cultural affinity is unknown.

The religious beliefs and practices of the Indus people remain largely mysterious. While some structures might have been temples, and some iconography might have religious significance, we cannot say with certainty what gods they worshipped, what myths they told, what rituals they performed. This is a profound gap in our understanding, as religion typically plays a central role in ancient civilizations.

The causes of the collapse remain debated. While climate change and environmental factors appear likely to have played a significant role, the relative importance of different factors—environmental change, social breakdown, economic disruption, disease, migration—cannot be determined with certainty. Different sites may have experienced the decline for different reasons, adding complexity to any unified explanation.

The fate of the population after the urban collapse is unclear. Where did the inhabitants of the cities go? How much of their culture survived in the communities that continued or formed in the post-urban period? Did they maintain any memory of their urban past, or was it forgotten within a generation or two?

These questions give the Indus Valley Civilization its haunting quality. We can walk the excavated streets, touch the bricks that hands laid over four thousand years ago, examine the seals carved with such care, trace the efficient drainage systems—but we cannot hear the voices of the people who built and lived in these cities. They remain tantalizingly close yet ultimately distant, visible in their material culture but silent in their own words.

Perhaps someday the script will be deciphered, and the civilization will speak in its own voice. Until then, it remains what it has been since its rediscovery: one of history’s most fascinating mysteries, a testament to both human achievement and fragility, a reminder that even great civilizations can vanish so completely that their very existence is forgotten.

The empty streets of the excavated cities, the silence of the undeciphered seals, the questions without answers—these are what remain of the Indus Valley Civilization. It was one of humanity’s first experiments with urban life, and for over a millennium, it succeeded brilliantly. Then it ended, not with dramatic conquest or catastrophic destruction, but with gradual abandonment, with cities slowly emptying and falling into disrepair, with a great civilization fading into silence and forgetting. The mystery of why—and what it means—continues to echo across the millennia.