Thunder from the South: How Mysore’s Iron Dragons Changed Warfare Forever

The night sky over the Deccan plateau erupted in trails of fire. Shrieking through the darkness came objects unlike anything the British soldiers had encountered before—iron cylinders belching flames, arcing across hundreds of yards with devastating accuracy. Some exploded on impact. Others careened wildly through the ranks, spreading panic and chaos. The British East India Company’s forces, accustomed to traditional warfare, found themselves facing a weapon that seemed to belong to another age entirely. These were the Mysorean rockets, and they were about to revolutionize warfare across the world.

The year was somewhere in the 1780s, and the Kingdom of Mysore had unleashed a technology that would ultimately travel from southern India to the battlefields of Europe, from the workshops of Indian craftsmen to the arsenals of Napoleon’s enemies. But on that night, as the rockets screamed overhead, the British soldiers cowering in their positions knew only one thing: they were facing something unprecedented, something that would haunt military strategists for generations to come.

The sound alone was enough to unnerve even veteran troops. A whistling crescendo that built from a distant hiss to a roaring shriek, followed by the impact—sometimes explosive, sometimes merely kinetic, but always terrifying. The psychological effect was as devastating as the physical damage. Horses bolted. Formations broke. Officers shouted orders that went unheard in the chaos. And through it all, more rockets came, launched in volleys that turned the night into day and the battlefield into an inferno.

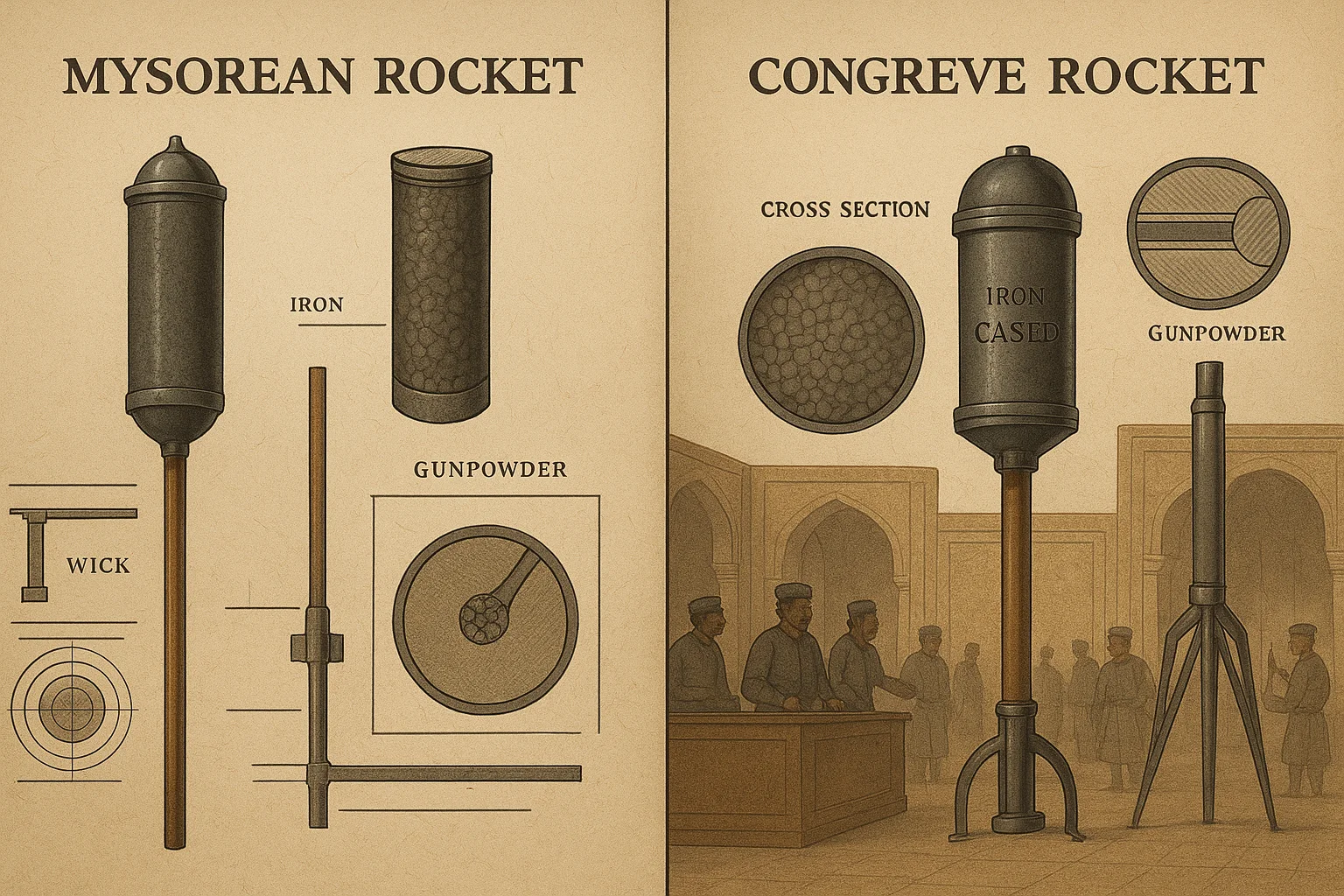

This was not the tentative experiment of curious inventors. This was organized, systematic military technology deployed by an army that had perfected its use over years of development and battlefield testing. The Mysorean rockets represented something extraordinary: the world’s first successful iron-cased rockets, and they were being used not as novelties or demonstrations, but as integral components of a sophisticated military strategy.

The World Before

To understand the revolutionary nature of the Mysorean rockets, one must first understand the state of warfare in the late 18th century. The Indian subcontinent was a patchwork of kingdoms, each vying for power, territory, and survival. The Mughal Empire, once the dominant force that had unified much of India under its rule, was in terminal decline. Regional powers had risen to fill the vacuum, and among the most formidable was the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India.

Traditional warfare of the era relied on infantry formations, cavalry charges, and artillery pieces that were heavy, slow to move, and required significant time to reload. Cannons could inflict tremendous damage, but their mobility was limited. Once positioned, they became fixed points around which battles flowed. Cavalry provided speed and shock value but was vulnerable to disciplined infantry fire. The technological equilibrium of warfare had remained relatively stable for decades.

Into this world had come the British East India Company, a commercial enterprise that had gradually transformed itself into a military and political power. What had begun as trading posts and factories had evolved into fortified settlements, then into territorial holdings, and finally into a force capable of challenging and defeating Indian kingdoms. The Company’s military power rested on European military discipline, superior musketry, and—increasingly—their ability to recruit and train Indian sepoys in European tactics.

The southern kingdoms watched this expansion with growing alarm. The Kingdom of Mysore, strategically positioned and economically prosperous, found itself directly in the path of British expansion. The relationship between Mysore and the British East India Company was complex and increasingly hostile. Trade relationships had given way to territorial disputes. Diplomatic tensions had escalated into military confrontations. The stage was set for a series of conflicts that would become known as the Anglo-Mysore Wars.

But Mysore possessed something that would distinguish it from other Indian kingdoms facing British expansion: a commitment to military innovation and a willingness to adopt and improve upon new technologies. The kingdom’s rulers understood that matching the British regiment for regiment, using identical tactics, was a path to eventual defeat. They needed something different, something that would offset British advantages and exploit British weaknesses.

The technology of rocketry was not unknown in India. Rockets had been used in warfare in various forms for centuries, though primarily as incendiary devices or psychological weapons rather than precision instruments of war. The critical limitation had always been the casing. Rockets wrapped in paper or cloth or constructed from bamboo had limited range, unpredictable trajectories, and minimal destructive power. They were spectacular but not strategically significant.

What Mysore needed was a way to transform the rocket from a novelty into a weapon system. They needed reliability, range, and power. They needed something that could be produced in quantity, deployed systematically, and used to genuine military effect. The solution would come from an unlikely source: iron.

The Players

The development of the Mysorean rockets is inseparably linked to two remarkable rulers: Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan. Their vision, their commitment to military innovation, and their willingness to challenge conventional thinking created the conditions in which this revolutionary technology could emerge.

Hyder Ali had risen to power in Mysore through military prowess and political acumen. His background was not that of traditional royalty, but rather of a skilled commander who had proven his worth on the battlefield and in administration. This outsider perspective may have contributed to his openness to innovation. He was not bound by tradition or by the assumption that warfare must be conducted as it always had been. When he looked at the military challenges facing Mysore, he saw not insurmountable obstacles but problems requiring creative solutions.

Under Hyder Ali’s rule, Mysore became something of a laboratory for military technology. He understood that the kingdom’s survival depended on its ability to field forces that could match or exceed the capabilities of its enemies. He invested in artillery, improved the training and organization of his infantry, and sought out new technologies and techniques from wherever they could be found. It was under his patronage that the systematic development of iron-cased rockets began.

The technical challenge was formidable. Iron casting was a known technology, but creating a casing that could withstand the tremendous pressures generated by the rocket’s propellant without being so heavy as to prevent flight required precision metallurgy. The powder composition had to be carefully formulated to provide sustained thrust without exploding prematurely. The design of the rocket’s exhaust nozzle was critical to achieving stable flight. The attachment of the guidance stick required exact balance.

Historical accounts do not provide the names of the individual craftsmen and engineers who solved these problems, but their achievement was remarkable. They created rockets with iron casings that could be manufactured consistently, filled with propellant that burned reliably, and launched with enough accuracy to be tactically useful. The rockets varied in size, with some accounts mentioning weapons ranging from a few inches to several feet in length, allowing for different tactical applications.

Tipu Sultan, who succeeded his father as ruler of Mysore, inherited both the kingdom and the commitment to military innovation. If anything, Tipu Sultan was even more enthusiastic about rocket technology than his father had been. He expanded the rocket corps, refined the tactics for their deployment, and ensured that the Mysorean army included substantial numbers of troops trained specifically in rocket warfare.

Tipu Sultan understood the multifaceted value of the rockets. They provided long-range strike capability without the mobility limitations of traditional artillery. They could be deployed in large numbers relatively quickly. They required less training to use effectively than conventional artillery pieces. And critically, they had a profound psychological impact on enemy forces. The sight and sound of a rocket barrage was unlike anything else in 18th-century warfare, and the terror it inspired was a weapon in itself.

The organization of the rocket corps reflected sophisticated military thinking. Rockets were not simply distributed randomly among the troops but were concentrated in specialized units with trained operators. These units could be positioned to provide supporting fire for conventional forces or used independently to harass enemy formations and disrupt their operations. The integration of rocket forces with traditional infantry and cavalry demonstrated a level of tactical sophistication that belied European assumptions about Indian military capabilities.

Rising Tension

The 1780s and 1790s saw the Kingdom of Mysore locked in a series of conflicts with the British East India Company. These Anglo-Mysore Wars were complex affairs involving not just Mysore and the British, but various alliances with other Indian kingdoms and European powers. The wars were fought for territory, for political dominance, and ultimately for the survival of Mysore as an independent kingdom.

It was in the context of these wars that the Mysorean rockets proved their worth. The exact details of their first use in battle are debated among historians, but what is clear from multiple sources is that the rockets were deployed effectively during the 1780s and 1790s. British forces found themselves subjected to rocket barrages that disrupted their formations, panicked their cavalry, and forced them to adapt their tactics.

James Forbes, a British observer whose accounts provide some of the most detailed contemporary descriptions of the Mysorean rockets, witnessed their use firsthand. His observations make clear that these were not experimental weapons being tentatively tried out, but rather established components of Mysore’s military arsenal, deployed systematically and to considerable effect.

The Battlefield Transformation

The use of rockets transformed battlefield dynamics in ways that challenged British tactical assumptions. Traditional warfare of the period involved relatively predictable patterns of movement and engagement. Artillery was positioned, infantry advanced or defended, cavalry maneuvered to exploit weaknesses. But rockets introduced an element of chaos and unpredictability.

A rocket barrage could be launched from positions that would be impossible for traditional artillery. The relative portability of the rockets meant they could be moved and repositioned more quickly than cannons. And unlike artillery, which fired in relatively flat trajectories and required direct line of sight to targets, rockets could arc high into the air, potentially reaching targets behind cover or fortifications.

The British response to the rocket threat evolved over time. Initially, there was confusion and disorganization. Traditional defensive formations offered limited protection against weapons that could fall from the sky at steep angles. Cavalry, normally a highly mobile and flexible force, proved particularly vulnerable, as horses were terrified by the rockets’ noise and unpredictable flight paths.

Over time, British commanders developed countermeasures. Dispersed formations reduced the concentration of troops vulnerable to a single rocket hit. Attempts were made to target the rocket launch positions with conventional artillery before the rockets could be fired. Rapid advances were sometimes employed to close the distance and engage Mysorean forces before sustained rocket barrages could be organized.

But the very fact that the British had to develop new tactics and countermeasures demonstrates the significance of the Mysorean rockets. This was not a weapon that could be ignored or dismissed. It was a genuine military innovation that forced one of the most powerful military organizations of the age to adapt and evolve.

The Technical Achievement

The successful development of iron-cased rockets represented a remarkable achievement in materials science and engineering. The challenges were not merely theoretical but intensely practical. How do you create an iron tube that can withstand the pressure and heat of the rocket’s propellant without rupturing? How do you seal the casing so that the expanding gases exit only through the designed exhaust, providing thrust rather than causing an explosion? How do you attach the guidance stick so that it remains securely in place during flight while not interfering with the rocket’s aerodynamics?

The solutions developed by Mysore’s craftsmen demonstrated sophisticated understanding of metallurgy, chemistry, and physics. The iron used for the casings had to be of sufficient quality and worked with enough precision to create reliable containers. The propellant composition had to be formulated to provide sustained burn rather than explosive detonation—a chemical challenge of considerable complexity.

The rockets’ design also showed evidence of systematic refinement and improvement. Variations in size and configuration suggest that different types of rockets were developed for different tactical purposes. Smaller rockets might have been used for harassment and disruption, while larger ones could deliver more significant explosive payloads. The existence of multiple variants indicates not a single invention but an ongoing program of development and enhancement.

The Turning Point

The Anglo-Mysore Wars ultimately ended with the defeat of Tipu Sultan in 1799, but the legacy of the Mysorean rockets extended far beyond the military fate of the kingdom. The British forces that had faced these weapons in battle did not simply forget them. On the contrary, the experience of being on the receiving end of rocket fire made a profound impression on British military thinking.

The conflicts with Mysore exposed the British East India Company—and through it, the broader British military establishment—to rocket technology in a way that could not be ignored. These were not theoretical weapons described in reports or treatises. They were weapons that British soldiers had faced in battle, weapons that had killed and wounded British troops, weapons that had disrupted British military operations.

After the fall of Mysore, British forces captured examples of the Mysorean rockets. These captured weapons were studied intensively. The iron casings were examined. The propellant composition was analyzed. The design principles were reverse-engineered. What began as an Indian military innovation became the foundation for European rocket development.

The man most associated with this technological transfer was William Congreve, a British artillery officer and inventor. Congreve studied the Mysorean rockets and used them as the basis for developing what would become known as Congreve rockets. The first successful Congreve rockets were developed in 1805—notably, after the British had been exposed to Mysorean rocket technology through their conflicts with the kingdom.

The Congreve rockets would go on to be used extensively by British forces in various conflicts, including the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. When British forces bombarded Fort McHenry in Baltimore in 1814, it was Congreve rockets that provided “the rockets’ red glare” immortalized in what would become the American national anthem. The technological lineage from the workshops of Mysore to the bombardment of an American fort represents one of history’s more remarkable examples of technology transfer.

The Recognition and the Irony

The British military’s adoption of rocket technology based on Indian innovation is one of the more striking examples of how colonial encounters influenced technological development. The narrative of European technological superiority, so central to colonial ideology, confronted a reality in which a significant military innovation had originated in an Indian kingdom and was subsequently adopted by European powers.

James Forbes and other British observers who witnessed the Mysorean rockets recognized their significance. Forbes’s accounts make clear that these were impressive weapons that had genuine military value. The decision to reverse-engineer and adopt the technology was an implicit acknowledgment that Mysore had developed something that British military technology lacked.

The development of the Congreve rocket was not simply a matter of copying the Mysorean design. British engineers made modifications and improvements, as one would expect. The Congreve rockets were somewhat different in design and performance from their Mysorean predecessors. But the fundamental concept—the iron-cased rocket used as a military weapon—was Indian in origin. The British had been introduced to this technology not through their own research or through reading about distant experiments, but through being attacked by it on the battlefield.

Aftermath

The immediate aftermath of Tipu Sultan’s death and the fall of Mysore in 1799 saw the dispersal of much of the kingdom’s military technology and expertise. The British consolidated their control over the region, and the independent Kingdom of Mysore ceased to exist as a significant military power. The rocket corps that had been such an innovative feature of Mysorean military organization was dissolved.

But the rockets themselves lived on, both as physical artifacts captured by the British and as knowledge that would shape military technology in Europe. The systematic study of the captured Mysorean rockets represented one of the first instances of what would become a common pattern: the transfer of technology from colonized regions to colonial powers, followed by the refinement and redeployment of that technology, often against other colonized peoples.

The development of the Congreve rocket proceeded rapidly once British engineers had access to Mysorean examples and design principles. William Congreve received considerable recognition and credit for his work on rockets, though the debt to Indian innovation was acknowledged by at least some contemporary observers. The Congreve rockets were tested, refined, and ultimately adopted by the British military as a standard weapon system.

The use of rockets spread beyond the British military. Other European powers took notice of this new weapon technology and began developing their own versions. The rocket as a weapon of war, pioneered in Mysore in the late 18th century, became a fixture of early 19th-century European military arsenals.

Legacy

The Mysorean rockets occupy a significant but often underappreciated place in the history of military technology. They represent the world’s first successful iron-cased rockets—a genuine innovation that emerged from Indian metallurgical expertise, chemical knowledge, and military necessity. The fact that they were developed in an Indian kingdom during the late 18th century challenges simplistic narratives about technological progress flowing unidirectionally from Europe to the rest of the world.

The technological lineage is clear: Mysorean rockets influenced the development of Congreve rockets, which in turn influenced subsequent rocket development in Europe and America. The iron-cased rocket as a weapon system can trace its origins directly to the workshops and arsenals of the Kingdom of Mysore. This is not a matter of speculation or nationalist mythmaking, but of documented historical fact acknowledged by contemporary observers and subsequent historians.

The broader significance of the Mysorean rockets extends beyond their specific technological innovations. They demonstrate that the late 18th-century Indian kingdoms were not technologically static or backward, but were capable of sophisticated innovation in response to military and strategic challenges. The stereotype of pre-colonial Indian warfare as primitive or unchanging cannot be sustained when confronted with the reality of systematic rocket development, production, and deployment.

The story of the Mysorean rockets also illuminates the complex dynamics of technological transfer in the colonial period. The flow of technology and knowledge was not simply from Europe to India, but in multiple directions. European powers learned from and adopted technologies they encountered in their colonial ventures, even as they maintained ideological commitments to European superiority. The Congreve rocket, celebrated as a British innovation, had Indian roots that were known to contemporary observers even if they were subsequently obscured in popular historical memory.

The effectiveness of the Mysorean rockets in actual combat is attested by multiple sources. They were not merely spectacular displays but weapons that had genuine military impact. They forced British commanders to adapt their tactics. They inflicted casualties and disruption on British forces. They demonstrated that Indian military technology could innovate in ways that challenged European military dominance.

What History Forgets

The story of the Mysorean rockets, despite its significance, remains less well known than it deserves to be. The reasons for this relative obscurity are complex and multifaceted. Part of the explanation lies in the broader patterns of how colonial history has been written and remembered. Technologies and innovations from colonized regions have often been underemphasized or attributed to other sources in historical accounts written from imperial perspectives.

The individual craftsmen and engineers who actually designed and manufactured the Mysorean rockets remain anonymous. Historical records preserve the names of kings and military commanders, but the skilled workers who solved the technical challenges of iron-cased rocket construction are lost to history. This is a common pattern in the historical record—the actual makers and inventors are often invisible, while credit and recognition flow to rulers and patrons.

The psychological and cultural impact of facing rocket fire in the late 18th century is difficult to fully recover from historical sources. Military records tend to focus on tactical details and outcomes rather than on the subjective experiences of soldiers under fire. But contemporary accounts suggest that the effect of rocket barrages was profound. The shrieking, unpredictable nature of rocket attacks created a level of stress and fear that went beyond the actual physical casualties inflicted.

The technical sophistication required to create effective iron-cased rockets is also often underestimated. Modern readers, living in an age of guided missiles and space rockets, may fail to appreciate how remarkable an achievement it was to create reliable iron-cased rockets using late 18th-century technology. The metallurgical precision, the chemical knowledge, and the design expertise all had to come together to produce a weapon that actually worked in battlefield conditions.

The relationship between Indian innovation and European adoption in the case of the Mysorean rockets provides a case study in how technology transfer actually worked during the colonial period. The simplistic model of European technology being transferred to India is complicated by examples like the Mysorean rockets, where the flow of technology was in the opposite direction. The British learned from what they encountered in India, adopted it, adapted it, and ultimately deployed it in ways that furthered British military power.

The broader context of Mysore’s military innovations tends to be overshadowed by the kingdom’s ultimate defeat. Historical narratives often focus on outcomes—who won and who lost—rather than on the innovations and adaptations that occurred along the way. Mysore lost the Anglo-Mysore Wars and ceased to exist as an independent power, but that military defeat should not obscure the technological achievements that the kingdom produced during its struggle for survival.

The Mysorean rockets also raise interesting questions about how military technology evolves. Innovation does not always come from the most powerful or dominant military forces. Sometimes it emerges from powers that are challenged and need to find ways to offset their opponents’ advantages. Mysore’s development of rocket technology was driven by strategic necessity—they needed weapons that could counter British military strengths. This pattern of innovation emerging from strategic pressure rather than from positions of dominance is a recurring theme in military history.

The fact that rocket technology developed in India in the late 18th century and then spread to Europe serves as a reminder that the history of technology is global rather than confined to any single region or civilization. Ideas, techniques, and innovations have always traveled, been adapted, and been combined with local knowledge and capabilities. The Mysorean rockets are part of this larger story of technological exchange and development.

When we look at the night sky lit by rocket fire over an 18th-century battlefield in southern India, we are witnessing not just a military engagement but a moment of technological innovation that would echo across continents and centuries. The iron casings crafted in Mysore’s workshops, the propellant formulas developed by its chemists, and the tactical doctrines created by its military commanders all contributed to a transformation in warfare that extended far beyond the immediate conflicts between Mysore and the British East India Company.

The Mysorean rockets stand as testament to Indian technological capability, to the creativity and expertise of craftsmen whose names we no longer know, and to the ways in which military necessity can drive innovation. They remind us that history is more complex than simple narratives of technological superiority or backwardness allow, and that the story of how humans have developed the tools of war is a story that spans cultures, continents, and centuries.

In the end, the thunder that echoed across the battlefields of southern India in the 1780s and 1790s was the sound of the future arriving. It was the sound of innovation challenging established power. It was the sound of iron cylinders screaming through the night sky, carrying with them the knowledge that would transform warfare around the world. The Mysorean rockets, the world’s first successful iron-cased rockets, were an Indian contribution to global military technology—a contribution that deserves to be remembered and celebrated as the remarkable achievement it was.