The Riddle of the Iron Pillar: Ancient India’s Metallurgical Marvel

The instrument reads the same as yesterday, and the day before, and every day for the past century and a half that scientists have tested this enigma. No rust. Not a flake, not a spot, not even a hint of the reddish-brown decay that devours ordinary iron with relentless appetite. The metal surface, dark and smooth as polished stone, reflects the morning sun in the courtyard of Delhi’s Qutb complex. Tourists press their backs against it for luck, a tradition whose origins are lost to time. Scientists press their instruments against it for answers, a quest that has frustrated metallurgists since the British first began systematic studies in the 19th century.

This is the Iron Pillar of Delhi—7.21 meters of impossibility, 41 centimeters in diameter, weighing approximately six tons. It has stood through sixteen centuries of monsoons, through Delhi’s suffocating summer heat and winter cold, through the reign of more than a hundred kings and the rise and fall of empires. It was already ancient when the first stones of the Qutub Minar were laid beside it. It had survived centuries when the Mughals made Delhi their capital. And through all these transformations of power, language, religion, and civilization, it has refused to rust.

The pillar keeps its secrets in plain sight, hiding advanced metallurgical knowledge in its very molecular structure—knowledge that the smiths who forged it sixteen hundred years ago possessed but never wrote down, techniques that were lost as surely as the pillar itself refuses to corrode. How did ancient Indian metalworkers, working without modern instruments, without electricity, without the theoretical framework of chemistry, create what modern science struggles to replicate? The answer is locked in the metal itself, in the careful proportions of elements, in the method of forging, in the wisdom of an age we have too hastily dismissed as primitive.

The World Before

In the year 400 CE, India stood at the zenith of classical civilization. The Gupta Empire, which had risen to dominance in the 4th century, presided over what historians would later call the Golden Age of India—a period of unprecedented prosperity, artistic achievement, and scientific advancement. While the Western Roman Empire tottered toward collapse, wracked by barbarian invasions and internal decay, the Indian subcontinent flourished under Gupta administration.

This was the age when the concept of zero was crystallized into mathematical notation, when the decimal system took its modern form, when Sanskrit literature produced works of enduring brilliance. The universities at Nalanda and Takshashila drew scholars from across Asia. Astronomers calculated the movements of celestial bodies with remarkable precision. Mathematicians worked on problems that would not be rediscovered in Europe for a thousand years. The Gupta court supported a renaissance of arts and sciences that touched every aspect of life, from medicine to metallurgy, from sculpture to statecraft.

The empire’s prosperity rested on more than intellectual achievement. The Gupta period witnessed remarkable advances in practical technology—agriculture flourished through sophisticated irrigation systems, trade networks stretched from Rome to China, and urban centers thrived as hubs of commerce and craft production. Iron working had been practiced in India for over a millennium by this point, evolving from the early bloomery furnaces of the Vedic period into sophisticated operations capable of producing high-quality steel in quantities that supplied not just domestic needs but export markets across the Indian Ocean.

Indian iron had already earned a formidable reputation. Greek and Roman sources mentioned Indian steel—what they called “Seric iron” or “wootz”—as among the finest in the world. Arab traders would later carry Indian blades throughout the Middle East, where they would be recognized for their superior hardness and ability to hold a keen edge. The famous Damascus blades, created from crucible steel imported from India, would become legendary for their quality. This was no accident of natural resources; the subcontinent’s ironsmiths had developed techniques of ore processing, carbon control, and heat treatment that represented the cutting edge of metallurgical science in the ancient world.

Yet even against this backdrop of achievement, the construction of the Iron Pillar would represent something extraordinary—not a weapon or a tool, but a monumental work of architectural engineering and artistic expression. The creation of a massive wrought iron structure, uniform in composition and free from the slag inclusions that typically weakened large iron objects, required mastery of every aspect of the metalworking process. From ore selection to final forging, every step demanded precision and skill honed over generations.

The world into which the pillar was born valued such demonstrations of technical prowess. Hindu kings, following traditions of dharma and kingship articulated in texts like the Arthashastra, were expected to undertake great works—temples, tanks, pillars—that demonstrated both their piety and their command of resources. A pillar of iron, towering and imperishable, served as a more than fitting monument to royal power and divine favor. It stood as a physical manifestation of stability and permanence in metal form, a vertical proclamation that would outlast stone itself.

The techniques required to create such an object—forge-welding pieces of iron into a seamless whole, maintaining consistent composition throughout tons of metal, creating a surface that would resist the oxidation that destroyed ordinary iron—these were not merely craft skills but represented deep understanding of materials and processes. The smiths who undertook this work stood at the pinnacle of a long tradition, benefiting from accumulated knowledge passed down through guilds and workshops over centuries. They worked in a civilization that valued such expertise, that organized labor and resources for monumental projects, and that preserved technical knowledge through apprenticeship and practice.

The Players

At the summit of this world of achievement stood Chandragupta II, called Vikramaditya—“Sun of Power”—the emperor who commissioned the Iron Pillar. The son of Samudragupta, himself a mighty conqueror, Chandragupta II inherited an empire at its height and expanded it further. Historical records credit him with subjugating the Western Kshatrapas, bringing the wealthy ports of Gujarat under Gupta control and connecting the empire’s heartland directly to the lucrative maritime trade of the Arabian Sea.

Chandragupta II’s court at Pataliputra (modern Patna) hosted the famous “nine gems”—the navaratna—a legendary circle of scholars and artists that included Kalidasa, whose poetry would define Sanskrit literature for all subsequent ages. The emperor himself was cultured, religiously tolerant, and politically astute. His reign represented the Gupta Empire at its most powerful and prosperous, controlling territory from the Bay of Bengal to the Arabian Sea, from the Himalayas to the Narmada River. The decision to create a monumental iron pillar came from this context of power and confidence, a ruler at the height of his authority commissioning a work that would proclaim his greatness to posterity.

Yet the true heroes of our story are not found in historical chronicles or royal genealogies. The smiths who forged the pillar left no names for history to record. They were master craftsmen of the lohar caste, metalworkers whose knowledge had been refined through generations of practice. In the workshops and forges of Gupta India, such men occupied positions of respect and importance. Their skills were essential to agriculture, warfare, and construction. The best among them served royal patrons, undertaking commissions that tested the limits of their craft.

To forge the pillar would have required not one smith but many, working in coordination under the direction of a master craftsman. The project would have drawn on the collective expertise of a workshop, possibly several workshops, with specialists responsible for different aspects of the process. Some would have overseen the smelting of iron ore, ensuring proper reduction to metal. Others would have managed the forging, the repeated heating and hammering that shaped the metal and welded pieces together. Still others would have handled the final shaping and finishing, the careful work that gave the pillar its final form.

These men worked without written formulas or theoretical understanding of chemistry. Their knowledge was empirical, built on observation and experience. They knew that certain ores produced better iron, that specific temperatures and techniques yielded desired results, that particular treatments made metal harder or more workable. This knowledge was preserved through demonstration and practice, passed from master to apprentice in the heat and noise of the forge. Much of what they knew was never written down because it was knowledge of the hand and eye, of judgment developed through years of practice, of subtle cues in the color of heated metal or the sound of the hammer striking the workpiece.

The exact location of the original forging is uncertain. Historical tradition and the pillar’s inscription suggest it was created in the eastern part of the empire, possibly near the capital at Pataliputra or at another major center of iron production. The completed pillar would have required transportation to its installation site—itself a considerable undertaking given its weight and length. The logistics of moving such an object across the distances of Gupta India, the organization of labor and resources required, speaks to the administrative capabilities of the empire as much as the technical capabilities of its craftsmen.

Supporting this enterprise was the entire apparatus of Gupta state power—the revenue system that funded such projects, the administrative hierarchy that organized labor and materials, the religious and cultural context that made such monuments meaningful. The pillar emerged from the intersection of imperial ambition, religious devotion, technical expertise, and organized state power. It required a civilization at its peak, capable of marshaling resources and knowledge for monumental undertakings.

Rising Tension

The challenge facing the Gupta smiths was unprecedented in scale. While the iron pillar was not the first large iron object created in India—iron beams had been used in construction, and substantial iron implements were common—the combination of size, uniformity, and artistic finish demanded by a monumental pillar pushed the boundaries of what was achievable with contemporary technology.

The first problem was one of sheer quantity. The pillar weighs approximately six tons. Creating this much workable iron required processing enormous amounts of ore. Ancient bloomery furnaces, the technology of the time, produced iron in relatively small quantities—typically blooms weighing a few kilograms to perhaps a few dozen kilograms. Each bloom had to be consolidated, refined, and shaped through repeated heating and forging to remove slag inclusions and create wrought iron of consistent quality. To accumulate enough refined iron for the pillar would have required the output of multiple furnaces over an extended period.

The second challenge was composition. Analysis of the pillar’s metal has revealed it to be remarkably pure wrought iron with a very low sulfur content and high phosphorus content—characteristics that contribute to its corrosion resistance. Achieving this composition throughout such a large mass of metal required careful selection of ore sources and consistency in processing. The smiths could not simply mix iron from different sources; variation in composition would create weaknesses and might affect the final properties of the metal. Someone had to make decisions about ore selection with an empirical understanding of how different sources would behave in processing and what properties the resulting iron would possess.

The third and perhaps most demanding technical problem was forge-welding. The pillar had to be constructed from many smaller pieces of iron, joined together to create a seamless whole. Forge-welding requires heating iron to near its melting point in a controlled atmosphere, then hammering the pieces together so that they fuse at the molecular level. Done properly, the weld is as strong as the parent metal. Done poorly, the joint remains weak and vulnerable to failure. To create a pillar 7.21 meters tall required numerous such welds, each executed with precision, building up the structure piece by piece.

The process would have been methodical and time-consuming. Working sections of iron would be heated in carefully tended furnaces, brought to the critical welding temperature—hot enough for the metal to fuse but not so hot that it burned or oxidized excessively—then quickly transferred to an anvil where teams of smiths would hammer it together with the growing pillar structure. The coordination required was immense. Timing was critical; the metal had to be worked while at the right temperature, requiring precise orchestration of furnace operations and forge work. Too slow, and the metal cooled below welding temperature. Too hasty, and the work might be sloppy, creating weak joints.

The Forge’s Rhythm

Imagine the scene in the Gupta forge during the pillar’s construction. The workspace would have been large, organized around one or more substantial furnaces capable of heating large pieces of iron. Teams of workers maintained the fires, feeding carefully prepared charcoal and managing air flow through bellows. The atmosphere would have been thick with smoke and heat, the air shimmering above the furnaces. The sound would have been tremendous—the rush of bellows, the roar of fires, the rhythmic clang of hammers on hot iron.

The master smith directed operations, his experienced eye reading the color of heated metal, judging when it reached the critical temperature for welding. At his signal, workers would withdraw a heated section from the furnace using long tongs. In choreographed motion, it would be positioned against the growing pillar, and immediately the hammers would begin their work. Multiple smiths working in coordination, their hammers falling in rhythm, would pound the joint, forcing the heated metals to fuse. Each hammer blow had to count; the working time was measured in moments before the metal cooled too much for effective welding.

This process repeated hundreds, perhaps thousands of times. The pillar grew incrementally, each welding session adding to its height and mass. As the structure grew taller, new challenges emerged. Working on the upper sections required scaffolding or platforms to position workers and handle hot metal at height. The base of the pillar had to support increasing weight without deforming. Every stage of the work demanded vigilance and skill.

The Mystery of the Formula

Hidden in this process was the secret of the pillar’s corrosion resistance, though it’s unlikely the smiths understood it in modern terms. The phosphorus content of the iron—higher than typical for ancient iron but carefully controlled—creates a protective passive layer on the surface in the presence of moisture. This layer, primarily composed of iron, oxygen, and hydrogen compounds, forms a barrier that prevents further corrosion. The low sulfur content prevents the formation of iron sulfide inclusions that would create weak points where rust could begin. The relatively pure composition of the wrought iron, with few slag inclusions, creates a uniform surface without the galvanic cells that promote corrosion when different metals or impurities are in contact.

But these are modern explanations, expressed in the language of chemistry and materials science. The Gupta smiths knew only that certain ores and techniques produced iron that resisted rust better than others. They had accumulated this knowledge through generations of empirical observation, noting which combinations of materials and methods yielded desired results. This was the wisdom of the workshop—practical, specific, and devastatingly effective, even if the theoretical foundations remained unknown.

The Turning Point

The completion of the pillar marked a triumph of coordination and skill, but the work was not finished. The completed iron column had to be moved to its installation site and erected—a feat of engineering that presented its own formidable challenges. Moving an object weighing six tons and measuring over seven meters in length across any significant distance required substantial infrastructure and labor.

Historical evidence suggests the pillar was originally installed elsewhere before being moved to its current location in Mehrauli. The pillar bears a Sanskrit inscription in Gupta script that provides crucial information about its origins and purpose, though the inscription’s details have been subject to varying interpretations by scholars. The movement of the pillar to Mehrauli likely occurred sometime after the decline of the Gupta Empire, possibly during the period of the Delhi Sultanate when Muslim rulers were establishing their authority over the region and incorporating existing monuments into new architectural complexes.

The erection of the pillar would have required substantial preparation. A foundation pit had to be excavated to adequate depth to support the pillar’s weight and height. The base of the pillar had to be positioned precisely vertical—any significant deviation from true vertical would compromise stability. Methods for raising such heavy vertical structures in ancient India typically involved ramps and lever systems, gradually tilting the horizontal pillar upward while sliding its base into the prepared foundation pit, then using ropes and human power to bring it to vertical position.

The technical challenges of this operation should not be underestimated. A seven-meter iron column, weighing six tons, represents a substantial load that must be controlled throughout the raising process. Loss of control could result in the pillar falling, potentially breaking and certainly endangering workers. The operation would have required significant labor—dozens of workers at minimum, possibly hundreds—coordinated in their efforts. It would have required ropes and timber for scaffolding and mechanical advantage, carefully positioned to distribute forces safely. And it would have required leadership from someone who understood the mechanics of the task and could direct the complex choreography of human effort.

The Standing Monument

When the pillar finally stood vertical, locked into its foundation, it represented more than a technical achievement. It was a statement—a proclamation in iron of the power and sophistication of the civilization that created it. The surface of the pillar bears decorative elements and the important Sanskrit inscription, details that would have been carefully executed by skilled craftsmen. The capital of the pillar, though damaged over the centuries, originally bore sculptural elements that enhanced its visual impact.

For the original viewers—subjects of the Gupta Empire encountering this monument—it would have been awe-inspiring. Iron was valuable, difficult to produce in quantity. A pillar of such massive proportions represented a stupendous investment of resources and labor. The fact that it was iron rather than stone emphasized the technological prowess of its creators. Stone pillars, impressive though they might be, were part of a ancient tradition extending back centuries. But an iron pillar of this scale was unprecedented, a demonstration of capabilities that pushed beyond existing boundaries.

The inscription on the pillar commemorates the victories and virtues of a king, identifying him with traditional Hindu symbolism and legitimizing his rule through both temporal achievements and cosmic order. The pillar served as a vertical text, a permanent record carved in metal that would endure for ages. That the medium of this record was rust-resistant iron proved prophetic—while stone inscriptions weather and erode, while palm-leaf manuscripts crumble and burn, the iron pillar’s message has survived largely intact across sixteen centuries.

Aftermath

The pillar’s existence through the subsequent centuries of Indian history reads like a chronicle of endurance. It stood through the decline and fall of the Gupta Empire in the 6th century, as political fragmentation returned to northern India. It witnessed the rise of regional kingdoms, the invasions of the Hunas, the emergence of new dynasties. Through all these transformations, the pillar remained—a mute witness to the passage of power and the changing fortunes of kingdoms.

When Islamic armies conquered northern India in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, establishing the Delhi Sultanate, they found the pillar at Mehrauli. Rather than destroying it—as happened to many Hindu monuments during this period of conquest—the new rulers incorporated it into their own architectural projects. The Qutub Minar, begun in 1199, rose beside the ancient pillar. The mosque of Quwwat-ul-Islam was built around it. The pillar became part of the new Islamic sacred landscape of Delhi, its original meaning reinterpreted or forgotten, but its physical presence preserved.

This preservation was not entirely accidental. Iron was valuable, and a pillar of such size represented a considerable quantity of metal. That it was not melted down for reuse suggests that it was valued for more than just its material content. Perhaps it was recognized as a monument of such antiquity and impressiveness that even rulers of different cultural and religious backgrounds appreciated its significance. Perhaps practical considerations—the difficulty of dismantling and melting such a large object—played a role. Or perhaps there was recognition among the artisan communities who served the new rulers that this pillar represented a technical achievement worthy of respect and preservation.

Through the centuries of the Delhi Sultanate, through the Mughal Empire’s rise and flourishing, through the various political upheavals that marked Delhi’s history, the pillar stood. Emperors and sultans came and went. Languages changed—Sanskrit gave way to Persian as the language of court and administration, later supplemented by Urdu and ultimately by English. Religions changed as Islam became the faith of rulers and significant portions of the population. Architectural styles changed as domes and minarets replaced the temple architecture of earlier eras. But the pillar remained, increasingly ancient, increasingly remarkable simply by virtue of its survival.

The Colonial Discovery

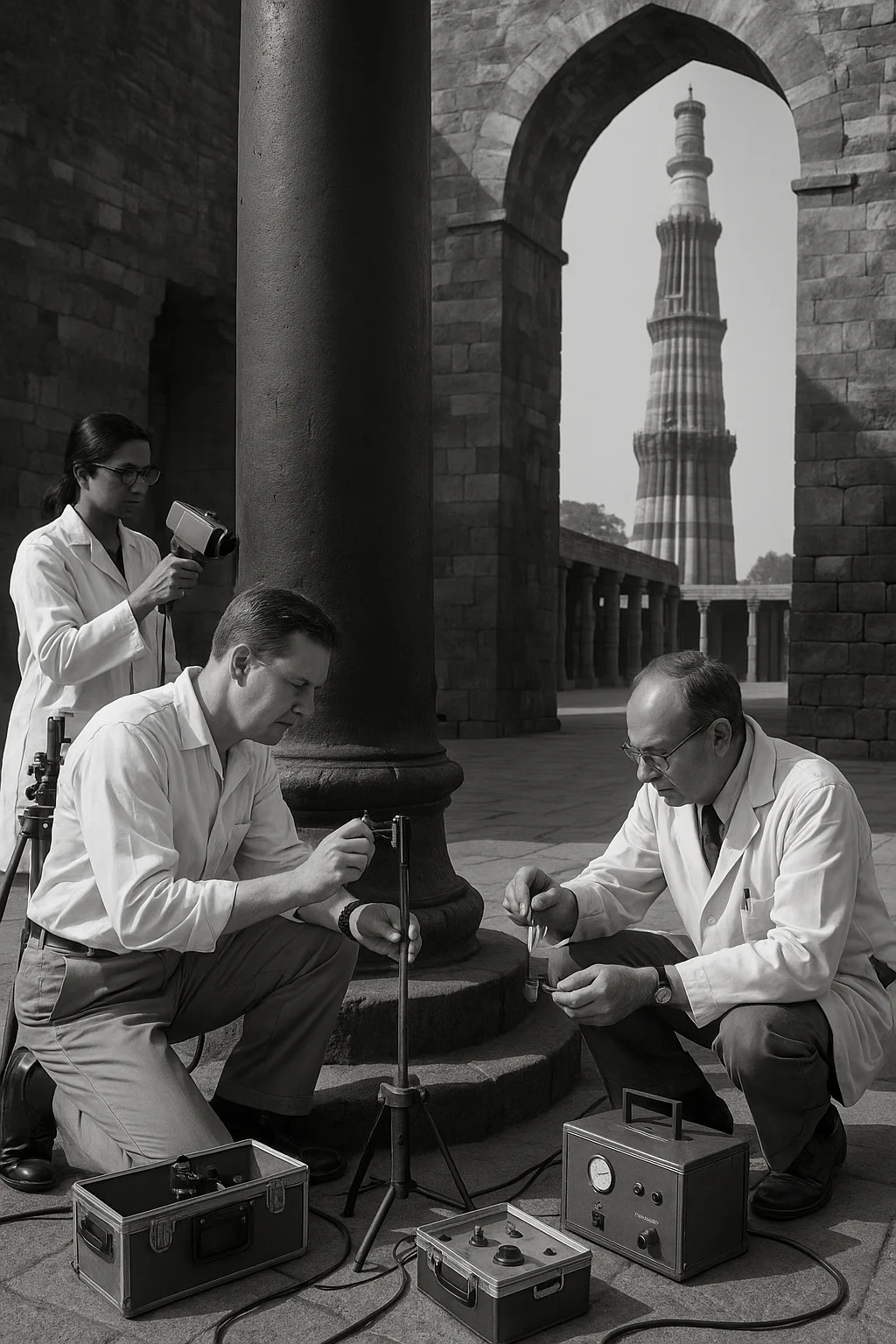

When British scholars began systematic study of India’s archaeological heritage in the 19th century, the Iron Pillar attracted immediate attention. Here was an artifact that challenged prevailing European assumptions about the capabilities of ancient non-European civilizations. The idea that Indian metalworkers sixteen centuries earlier could create a massive iron structure that resisted rust seemed almost incredible to observers whose own understanding of metallurgy was framed by the relatively recent Industrial Revolution.

Early British commentators expressed puzzlement and admiration. How had this been done? What techniques were used? Why hadn’t the pillar rusted like ordinary iron? Various theories were proposed, some fanciful, others more carefully considered. The pillar became a focus of scientific investigation, with researchers analyzing metal samples, measuring dimensions, studying the inscription, and attempting to reconstruct the methods of its creation.

These investigations yielded important information about the pillar’s composition and structure, but complete understanding remained elusive. The combination of factors that gave the pillar its remarkable corrosion resistance—the phosphorus content, the purity of the iron, the absence of sulfur, the uniformity of composition, the protective passive layer that forms on the surface—took decades of research to fully characterize. Even today, with all the tools of modern materials science, some questions remain about the precise techniques used in the pillar’s creation.

Legacy

The Iron Pillar stands today in the Qutb complex, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, visited by thousands of tourists annually. It remains one of Delhi’s most distinctive monuments, remarkable both for its age and for its seemingly impossible preservation. Modern visitors, like their counterparts across sixteen centuries, are drawn to touch it, to photograph it, to marvel at its existence. The tradition of pressing one’s back against the pillar and trying to encircle it with one’s arms—once believed to bring good luck or fulfill wishes—continues, though conservationists increasingly worry about the cumulative effects of so much human contact.

For historians of science and technology, the pillar represents invaluable evidence of ancient Indian metallurgical capabilities. It demonstrates that sophisticated iron-working techniques existed in India by the 5th century CE, confirming literary and archaeological evidence of Indian expertise in metallurgy. The pillar stands as physical proof that advanced practical knowledge can exist and be effectively applied without modern theoretical frameworks—that empirical observation and accumulated craft wisdom can achieve results that still impress and perplex.

The pillar has inspired modern research into corrosion-resistant materials. Scientists studying the mechanisms that preserve the pillar have gained insights applicable to contemporary materials science. The understanding that phosphorus-rich iron forms protective passive layers has influenced approaches to corrosion prevention. While modern technology has developed various methods for protecting iron and steel—galvanization, specialized alloys, protective coatings—the ancient approach embodied in the pillar remains elegant in its simplicity and effectiveness.

For India itself, the pillar serves as a powerful symbol of historical achievement in science and technology. In a post-colonial context, where narratives of European technological superiority long dominated historical understanding, the pillar stands as concrete evidence of indigenous innovation and expertise. It has become an icon of ancient Indian scientific advancement, appearing in textbooks, on stamps, in museums, and in popular culture as a reminder that India’s contributions to global knowledge and technology have ancient roots and substantial depth.

The pillar also raises important questions about the transmission and loss of technical knowledge. The smiths who created it possessed skills and understanding that subsequent generations apparently did not fully preserve. This loss was not unique to India—throughout human history, technical knowledge has been gained and lost, flourishing in some eras and places while declining in others. The collapse or transformation of political systems, changes in economic patterns, shifts in what society values and supports—all these can disrupt the transmission of specialized knowledge.

The fact that we cannot easily replicate the pillar’s creation with traditional techniques, even with our advanced theoretical understanding, highlights a fundamental truth about craft knowledge: much of it is tacit, residing in skilled practice rather than explicit theory. A modern metallurgist, armed with knowledge of chemistry and materials science, could specify the composition of a rust-resistant iron. But translating that specification into practice using 5th-century technology—selecting appropriate ores, managing bloomery furnaces, executing forge welds on the necessary scale—would require redeveloping the practical skills that ancient smiths spent lifetimes mastering.

What History Forgets

What often gets lost in discussions of the Iron Pillar is the human dimension—the daily reality of the work that created it. The historical record preserves the name of the emperor who commissioned it and the general time period of its construction. But the men who actually forged it remain anonymous. Their names were not carved in stone or preserved in chronicles. Their stories are lost. Yet their skill and labor created an object that has outlasted empires.

Consider the younger apprentices in the workshop, learning their craft through observation and practice. For them, working on the pillar project would have been a formative experience—a chance to participate in a major undertaking, to learn from master smiths, to develop skills that would define their own careers. The successful completion of the project would have enhanced the reputation of the workshop, leading to future commissions and continued prosperity. The techniques learned and refined during the project would have been passed on to the next generation, contributing to the continuing tradition of metalworking excellence.

Consider also the toll of the work. Forging iron is physically demanding and dangerous. The heat of the furnaces, the heavy hammering, the risk of burns and injuries, the long hours of intense concentration—all these extracted a price from the workers. Some may have been injured during the project. The master smiths who directed the work carried enormous responsibility; failure would have meant loss of resources, loss of reputation, possibly loss of patronage. The pressure to succeed must have been immense.

The pillar’s inscription mentions neither these workers nor their struggles. Royal inscriptions commemorate kings and their deeds, not the artisans whose skills made those deeds possible. This is a pattern repeated throughout history—the erasure of labor from the historical record, the attribution of achievement solely to royal patrons rather than to the combination of patronage and skilled execution that actually produces monumental works. Yet the pillar itself testifies to the excellence of its makers. Their names may be forgotten, but their work endures.

Another forgotten dimension is the economic context. The resources required to create the pillar—the ore, the fuel for furnaces, the labor, the time—represented a significant economic investment. This investment came from the surplus wealth generated by the Gupta Empire’s agricultural and commercial economy. The pillar was made possible by the productive labor of farmers, merchants, artisans, and workers throughout the empire whose taxes and economic activity generated the revenue that funded royal projects. The pillar, in this sense, represents not just the skill of metalworkers but the economic vitality of an entire civilization at its peak.

Finally, there is the question of what else might have been lost. If 5th-century Indian smiths could create a rust-resistant iron pillar, what other technical achievements might they have accomplished? What other knowledge might have existed in their workshops, in the oral traditions of their guilds, that was never written down and subsequently lost? The pillar survives as a testament to what was achieved, but it also serves as a reminder of how much we don’t know about ancient technical capabilities. The written record is fragmentary; physical evidence is partial. Much of the technological heritage of ancient civilizations has vanished, leaving us with tantalizing hints and isolated examples rather than comprehensive understanding.

The Iron Pillar of Delhi stands today as it has stood for sixteen centuries—a riddle in metal, a testament to lost expertise, a reminder of human ingenuity and skill. It has outlasted the empire that created it, the language in which its inscription was carved, the religious and cultural context that gave it meaning. Through invasion and conquest, through the rise and fall of dynasties, through colonization and independence, it has endured. Scientists continue to study it, tourists continue to photograph it, and it continues to resist the rust that devours ordinary iron. In the shadow of the Qutub Minar, surrounded by the remains of other ages and other empires, it stands—ancient, inexplicable, and enduring—a permanent question mark forged in rust-resistant iron, asking us to reconsider what we think we know about the capabilities of our ancestors and the nature of technological achievement.